Some people never learn from others' mistakes. Or maybe they let their ideological zeal overwhelm sound judgement. Either way, discrimination in hiring, promotion, and college admissions under the rubric of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) has run amok, and its shortcomings are obvious.

The most recent is the Federal Aviation Administration's diversity and inclusion hiring initiative on the agency's website, which spells out that it is actively seeking to hire workers with "disabilities that the Federal government, as a matter of policy, has identified for special emphasis in recruitment and hiring." Those "targeted disabilities" include "hearing, vision, missing extremities, partial paralysis, complete paralysis, epilepsy, severe intellectual disability, psychiatric disability and dwarfism." (Emphasis added.)

First during medical school and again during my years as a medical officer and office director at the Food & Drug Administration, my own experiences convinced me that such initiatives are unwise and potentially dangerous, particularly when the bean-counters are committed to them.

When I entered medical school at the University of California, San Diego, in the 1970s, a requirement for graduation was passing both parts of the medical board exams, the "medboards." Part One tested knowledge of basic science; Part Two, clinical medicine. For several years, the medical school had conducted an aggressive program of recruiting and admitting underqualified minority students. It turned out that they were able to scrape by on Part One, but many were failing Part Two.

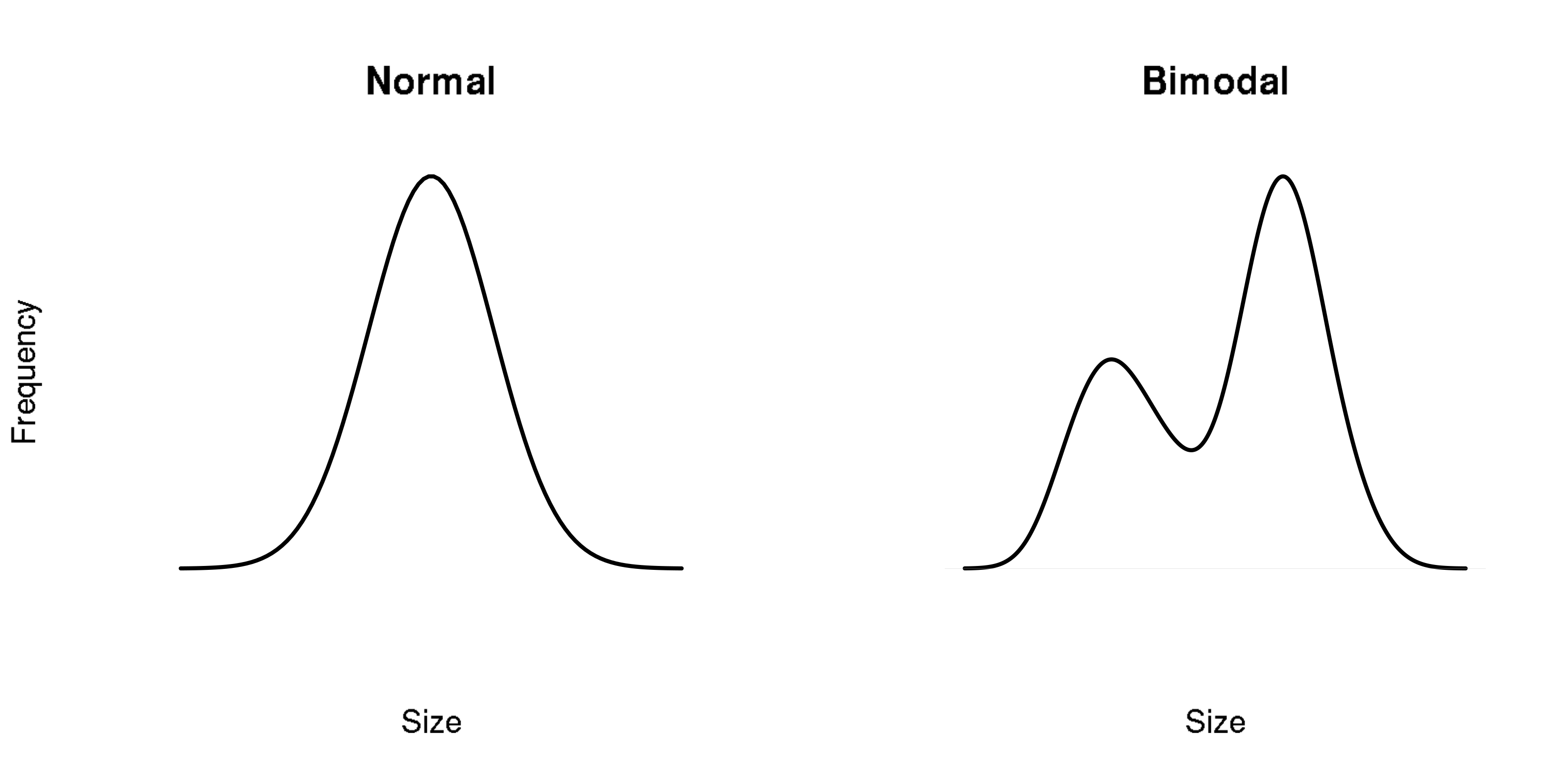

That was not a surprise. Grades on exams were posted, not by students' names but as curves. Ordinarily, you would expect the grades to fall in what's called a "standard normal distribution" that looks like the curve on the left. Instead, the distribution was often a "bimodal" curve, like the one on the right:

That implied, correctly, that there were two distinct populations represented by the scores, and we quickly ascertained that the lower distribution consisted of the underqualified minority students.

Instead of tightening the admissions criteria, the administration's response was to lower the graduation requirement to passing Part One and just taking, but not necessarily passing, Part Two. Nary a peep was heard from the faculty.

This sort of manipulation at medical schools has not been uncommon. Stanley Goldfarb, M.D., a retired dean for curriculum and co-director of the renal division at the University of Pennsylvania's medical school, has repeatedly criticized the trend toward allowing "social justice" considerations to play a dominant role in medical schools' admissions and curriculum. He founded a nonprofit called Do No Harm, whose purpose is "to combat discriminatory practices in medicine."

Consider this: When you're admitted to the hospital for complicated cardiac or neurosurgery, do you want it to be done by the most competent and accomplished surgeon or by one who was admitted to medical school and residency because he or she was a member of an underrepresented group?

While I was a medical officer at the FDA, my division had a secretary who was obviously incompetent – suffering an "intellectual disability," in the words of the FAA's recruiting initiative. She would hand me phone message memos with phone numbers that had only six digits and would insist that that was what the caller had told her. Another employee in the division, a Consumer Safety Officer, was a paranoid schizophrenic who would frequently barricade himself in his office and refuse to come out. The division director repeatedly tried unsuccessfully to fire him. These were examples of our tax dollars at work – long before efforts to specifically recruit such people.

Another example emerged from a Clinton administration initiative that had federal agencies hiring minority students part-time from Washington, DC high schools to inculcate in them a real-world "work ethic." I was an office director and, against my better judgement, agreed to take on a "straight A" student. Well, "Kamala" was unmotivated and unintelligent and, especially after she got pregnant, spent much of her "work day" talking on the phone to her friends. I asked our administrator several times to terminate her, but she demurred, saying it would "make the Agency's numbers look bad."

Finally, one day, my secretary came into my office, closed the door, and told me that Kamala was using our federal pre-paid overnight-mail envelopes to send messages to her boyfriend. I picked up the phone, called the administrator, and told her that if Kamala returned to the office, I would feel duty-bound to report her theft of federal property to the FBI. I never saw Kamala again.

So much for federal recruiting programs that target "underrepresented minorities" and the "intellectually disabled."

Finally, back to the FAA... How would you feel about having a paranoid schizophrenic or someone with a "severe intellectual disability" acting as the air-traffic controller landing the plane at the end of your next flight?

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger Distinguished Fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. He was the founding director of the FDA's Office of Biotechnology.