There's an old joke about the drunk who's hunting for his lost keys under the lamppost, not because he thinks they're there, but because the light is good. Well, that's what the feds and state governments are doing to try to quell the epidemic of opioid addiction and overdoses.

The problem is quite real, but legislators and regulators are making incorrect assumptions and adopting flawed strategies. And then, there are some flawed clinical studies and statements by the U.S. surgeon general that conspire to create misunderstanding of the landscape.

For a start, the problem isn't currently prescribed opioids, such as fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone. A study published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine found that from 2012 to 2017, a time when the overdose death rate was markedly accelerating, the rate of opioid prescriptions in patients who had not previously used opioids fell 54%, a decline driven by a decreasing number of prescribers.

More evidence was provided by a February article in the journal JAMA, which concluded that "under current conditions, the opioid overdose crisis is expected to worsen — with the annual number of opioid overdose deaths projected to reach nearly 82,000 by 2025, resulting in approximately 700,000 deaths from 2016 to 2025." But here's the rub: In the predictive model, preventing prescription opioid misuse alone would have only a modest effect — a few percent — on lowering overall opioid overdose deaths in the near future.

In spite of such findings indicating that the crux of the problem is not physician-prescribed opioids but illicit fentanyl and its analogs smuggled from abroad, like the drunk in the parable the feds and state governments are looking in the wrong place.

The extant problem has been exacerbated by the law of unintended consequences and the law of supply and demand. As a result of federal policies, some of our most important and potent analgesics, including fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone, which are commonly used in patients with advanced cancer and for pain control after surgery, are now in shortage, according to the FDA. All of these drugs had their manufacturing quotas reducedby the DEA, as if, in any case, it's the government's business to tell companies what and what not to manufacture.

The feds misunderstand the role of opioids in providing relief from significant pain — such as from kidney stones, sciatica, cancer, or broken bones, which can be excruciating — but they are not entirely to blame. Academics have also contributed — for example, a 2017 article in JAMA Network by Chang et al. The study is so poorly designed that we can only conclude that the investigators intended to get a desired, albeit inaccurate, result — namely, that acetaminophen (brand name: Tylenol) and ibuprofen (brand name: Advil) are as effective pain relievers as opioids alone or opioids in combination with acetaminophen.

If they were real, these findings would be hugely important, because opioids could be supplanted by widely used, over-the-counter analgesics. For that reason, it is worth enumerating the flaws — or, more precisely, tricks — in the study.

The study included four groups of people in pain (416 total) who were seen at either of two emergency departments at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx between 2015 and 2016. The four groups that were compared:

- Group 1 received 400 mg of ibuprofen plus 1,000 mg of acetaminophen

- Group 2 received 5 mg of hydrocodone and 300 mg of acetaminophen

- Group 3 received 5 mg of oxycodone plus 325 mg of acetaminophen

- Group 4 received 30 mg of codeine and 325 mg of acetaminophen

There are several problems with the study design:

1. Dose.

- The maximum therapeutic single dose of ibuprofen is 400 mg. (Doses higher than 400 mg have not been shown to be more effective.)

- The maximum recommended single dose of acetaminophen is 1,000 mg. Higher doses can cause irreversible liver damage.

- The usual adult dose of hydrocodone is 5-10 mg.

- The usual adult dose of oxycodone is 5-15 mg.

- The usual adult dose of codeine is 15-60 mg.

It appears that the study was designed to compare the analgesic power of the highest permitted dose of ibuprofen and acetaminophen with the lowest effective doses of hydrocodone and oxycodone. That's not playing fair. If this trial had been performed with realistic, instead of barely therapeutic, opioid doses we would expect to see very different results.

2. Selection criteria. The study group was limited to patients with acute extremity pain — "pain originating distal to and including the shoulder joint in the upper extremities and distal to and including the hip joint in the lower extremities." If the patients had been experiencing really intense pain from, say, kidney stones or severe sciatica, ibuprofen and acetaminophen would hardly touch it.

3. Opioids to the rescue — for some. Approximately 18% of the patients received "rescue analgesia." In other words, when the initial treatment failed, the patient was given oxycodone or morphine. A total of 73 patients didn't get adequate relief from either ibuprofen/acetaminophen or low-dose opioids, but the authors do not indicate which therapy failed.

4. We wonder why those patients were given insufficient pain medicine in the first place. And we believe that the rescue data indicate that opioids are superior for pain relief: The 73 did not get "rescue acetaminophen" because a) some of them had already been given the maximum dose, and b) literature reviews have shown that acetaminophen is pretty worthless as an analgesic.

We can't help wondering why anyone in an emergency room with "moderate to severe acute extremity pain" would agree to be part of a study in which three-quarters of the patients weren't going to receive an opioid. We suspect that there's not a compos mentis physician in the world who would volunteer to be a patient in such a study.

Thus, the Chang et al study appears to have been more about ideology than medicine. And just this month, we had a painful sensation of déjà vu — courtesy of no less a personage than Dr. Jerome Adams, the U.S. surgeon general. On July 3, he tweeted:

We'd like very much to hear directly from the patients, especially those with significant post-operative pain who were given Tylenol.

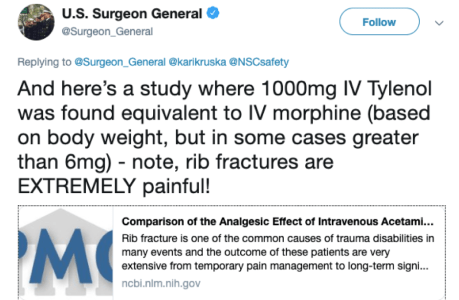

A day later, Adams was at it again:

Does Tylenol relieve pain better than morphine? Count us as skeptical. Adams was referring to a 54-person randomized clinical trial of pain control following rib fractures, which are notoriously painful. The trial, which was conducted in an emergency department in Iran, compared intravenously administered Tylenol (,1000 mg) and morphine (0.1 mg per kilo of body weight). Supposedly, the result was that Tylenol relieved pain as well as intravenous morphine in patients with rib fractures — but even a cursory reading of the article, which was published in the obscure journal Emergency (Tehran), reveals that it demonstrates no such thing.

Basically, that study found that 30 minutes post-administration of drug, the mean pain score on a scale of 1-11 was 5.5 for the morphine-treated patients and 4.9 for the Tylenol-treated patients. That supposed difference was the entire basis for Adams' claims of equivalence of Tylenol and morphine — except that the data aren't even close to being statistically significant: p = 0.23. (Statistical significance would be p<0.05.) In plain language, one cannot conclude from this study that Tylenol is equivalent to morphine.

There were many other deficiencies in the design of the study. For example, there was no control group, so it can't be determined whether the observed reductions in pain score were due to drug or to a placebo effect. Also, the initial pain score of both groups was supposedly "the same," but with p = 0.19, this may or may not be true. It can't be determined whether the group that received began the study with more pain, less pain, or no difference, confounding the interpretations of the results.

Moreover, the success rate (defined as a three percentage-point reduction in pain score) was 80% for Tylenol and 59% for morphine. That difference also fails statistical significance: p = 0.09. Even the authors acknowledge that. Thus, from this study, there is simply no evidence that Tylenol and morphine are equivalent — something that Adams should have known.

Perhaps more baffling about the study is that when there was a treatment failure after 30 minutes (inadequate pain relief), morphine was given as a rescue therapy. This automatically skews the results. It's like saying "Tylenol works as well as morphine except when it doesn't." Nor do the authors tell us how often rescue therapy was given.

Finally, there was this: "Presentation of side effects was similar in both groups."

That is hard to explain. We've been hearing for a decade how dangerous opiate analgesics are, but there was no difference in side effects between the Tylenol and morphine groups? The fact that the patients who received morphine did not report nausea or dizziness suggests that morphine was either not used at all, or used at a sub-therapeutic dose.

The surgeon general's claim that intravenous Tylenol works as well as morphine was unsupported and irresponsible. (He has subsequently deleted the tweet.)

The evidence continues to accumulate that the government's opioid policies — and pronouncements — need adult supervision. We are not optimistic that it will materialize.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a senior fellow at the Pacific Research Institute. He was the founding director of the FDA's Office of Biotechnology. Josh Bloom is the director of chemical and pharmaceutical science at the American Council on Science and Health. He has a Ph.D. in chemistry.